Everyone is pretty quick to jump on the bandwagon and call the awesome new find in Denmark a ‘valkyrie’. I’ll admit, this stunning little 3D figurine of a woman with some sort of dagger and shield is fantastic, and it is tempting to turn to the mythological texts and slap the big fat ‘V-word’, on her forehead. But despite newspapers such as The Guardian openly lauding: ‘the only 3D representation of a valkyrie ever found’, and many medieval bloggers going nuts over the ‘unique silver valkyrie’, found in Hårby, Fyn (Denmark), can we really call this figurine a ‘valkyrie’, with such sure-fire confidence? I hate to be the moany voice of reason, but I feel a semi-critical eye would be of use here. I’d like to urge caution and consideration before calling this figurine a ‘valkyrie’, straight off.

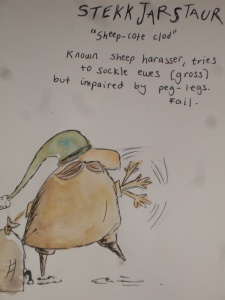

The ‘valkyrie’ found recently in Denmark, thought to be from c. 800 AD

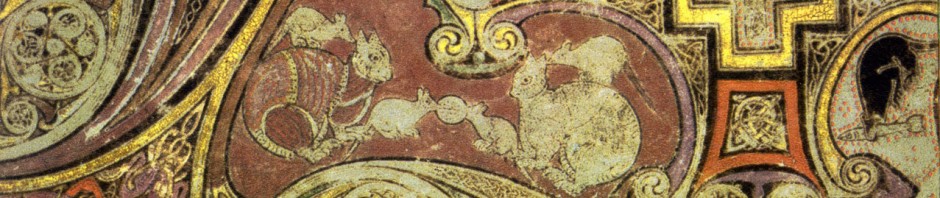

Of course, in many respects, this little figure ticks all of the boxes: turning to the mythological descriptions of valkyries written down in 13th-century Iceland, there is clearly a strong oral poetic tradition linking the valkyrie to battle. ‘Kennings’, which are normally used in a poetic sense as a round-about way of saying things (almost like an uber-allusive metaphor), are popping at the seams of Old Icelandic skaldic verse. It is in these kennings that valkyrie names often occur. Take, for instance, the kenning: veðrum Göndlar (‘the winds of Göndul > valkyrie) or Hildr hjaldrs (‘the Hildr > valkyrie of battle’). The substitution of a valkyrie name for the meaning ‘battle’, convincingly points to an association of such women with warfare. Even the word valkyrie in Old Norse means ‘chooser of the slain’, and many of the valkyries cropping up in the Poetic Edda are described as wearing armour or doing battlely-like things.

Yet the presentation of the valkyrie is not always consistent within eddic mythology and skaldic verse. In the eddic poem Sigdrífumál, for example, the valkyrie Sigdrífa imparts knowledge of runic lore and wisdom to the hero Sigurðr; she has nothing to do with giving victory in battle. Similarly, the most famous valkyrie, Brynhildr, is known more for her passionate love entanglements with Sigurðr and Gunnar than rampaging about on the battle field. Whilst Snorri Sturluson’s prose account of Norse mythology explicitly says that Óðinn sends his female entourage out onto the battlefield, he also notes (probably with misogynistic glee) that she is also given the glamorous job of barmaid: she is a waitress for the drunken dead in Valhöll, serving them drink and keeping the cutlery nice and tidy.

Of course, what a 13th century Icelandic scribe, compiler or writer says about a valkyrie is somewhat removed (and modified by various changing social, religious and political conditions) from a 9th century, Danish perception of a valkyrie. This is exactly my point. The Old Icelandic texts are useful, as they give us access to words which we can try to apply to pictures, figures and finds unearthed by archaeology: yet in all the pictorial representations of ‘valkyries’ that we have, none of them have a note scribbled underneath saying: ‘psst, by the way, did you know that I’m actually a valkyrie?’. Just because they have a mead horn in their hand, for example, it doesn’t make them a valkyrie: the giantess Gerðr, for instance, is known to offer mead, as does the goddess Sif and various other non-valkyrie figures.

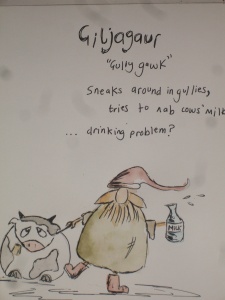

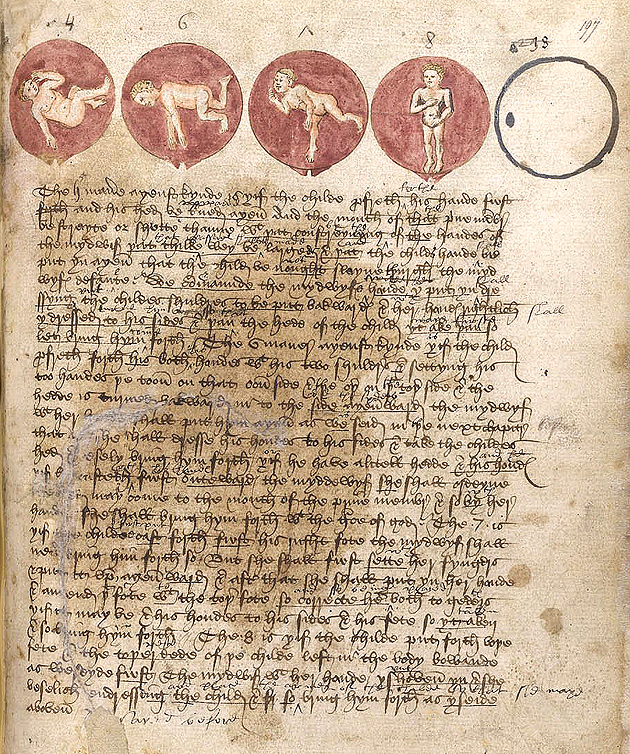

a guldgubber depicting a woman with a hair-knot and a drink

In fact, the images of mythological women that we have from the late Iron Age to beginnings of the Christian period in Scandinavia are all remarkably similar, making them incredibly difficult to pin down to a particular type of or individual mythological ‘woman’. The Gotland picture stones often depict women welcoming male figures with what looks like a mead horn. She is noted for her long dress and recognisable ‘top knot’ hair-do (a proto-hipster, perhaps?). Similarly, the gorgeous little gold-foil finds called ‘guldgubber’, often represent women with a similar hair-do, sometimes with a mead horn in her hand. It is impossible to say whether these images represent valkyries, goddesses, dísir or other supernatural beings, and it is not impossible that each one had its own meaning for the local community or individual using/crafting it.

Yet, despite being separated over time and space, these images all persist with the same general motif. This is what makes our new ‘valkyrie’ figure so interesting: she is the first 3D find of her type, she has the same ‘hair knot’, motif but, instead of a mead horn, she is holding a shield and sword. She is perhaps, with her associations of battle, the closest thing to what the 13th-century Icelandic texts might call a ‘valkyrie’. But ideas and perceptions of images change over time, and it is impossible to say exactly what 9th century Danes (or whoever made/observed this figure) considered this woman to represent. Admittedly, it is nice to think of this new find as a battle-maid of Óðinn, but in all honesty I’m not sure that we can call her a ‘valkyrie’ so easily and comfortably without really looking into the range of literary and iconographic depictions of valkyries first. Only then can we tentatively suggest how this new archaeological find fits in amongst the already huge, kaleidoscopic variety of female mythological figures we have available to us. But still, it is pretty awesome – and everyone should check it out when it comes to the British Museum, 2014!

A link to the Guardian’s article: http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2013/mar/04/viking-valkyrie-figurine-british-museum